How a fertilizer shortage may boost chicken over beef

Navigating current economic conditions sometimes can feel like a walk through a funhouse filled with mirrors of price and supply distortions. Down one such hallway we explore how shortages of fertilizer in 2022 may lead to a bright future for chicken and a less promising future for beef.

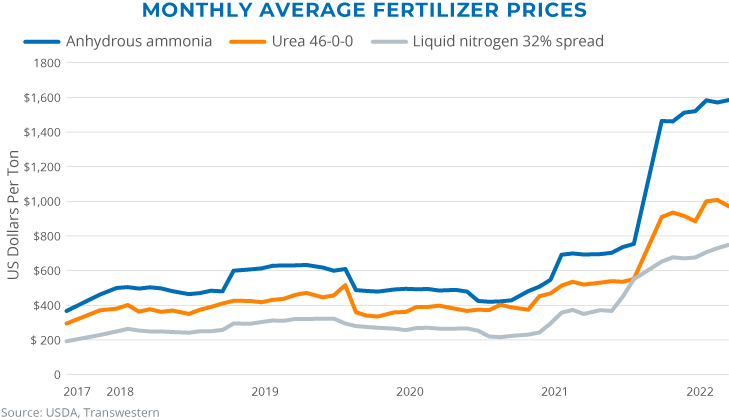

Fertilizer prices have risen worldwide.

The global population grew from 3 billion in 1960 to 7.9 billion in 2022 and has been supported by advances in agricultural productivity such as genetically modified plants and chemical fertilizers. Fertilizer turns soil into the powerhouse of agricultural production the world depends on, and changes in its availability and/or pricing can lead to profound market shifts.

Russia is the world’s largest exporter of fertilizer, and the United States is the world’s third largest importer. Supply chains on both sides have been disrupted by global events. The U.S. is also a major manufacturer of nitrogen fertilizer, which requires large inputs of energy and natural gas to produce. Higher energy prices and trade restrictions have led to sharp reductions in fertilizer supplies impacting consumers in unexpected ways.

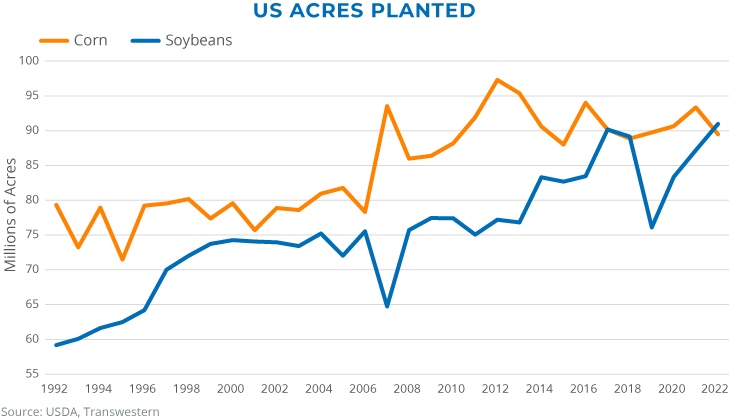

Profitable use of fertilizer changes what is planted.

The U.S. is the world’s largest producer of corn and the second-largest producer of soybeans. Historically, more acreage has been dedicated to corn, which has traditionally commanded higher prices and is more heavily subsidized. Corn, however, requires more fertilizer than soy, leading to higher upfront costs. As a result, 4% less corn was planted in 2022 (89.5 million acres), with a corresponding 4% rise in soy production (a record high of 91.0 million acres). That means less corn and more soy, at least for now.

U.S. corn has three main uses: Ethanol, high-fructose corn sugar and livestock feed. Ethanol is used as a fuel additive to decrease pollution, corn sugar finds its way into many products including soft drinks, and corn feed is used for beef and chicken. Corn is commonly measured by the bushel, which is roughly 8 U.S. gallons. One bushel can produce 2.7 gallons of ethanol, sweeten 400 cans of soda, produce 6 lbs. of beef or 20 lbs. of chicken. Corn is used heavily in beef feedlots to fatten up cows in their final months.

U.S. soy is used for animal feed, vegetable oil and biodiesel. Approximately 37% of the world’s soy is used as poultry feed, with beef accounting for only 0.5%. Soybeans are among the best sources of plant-based protein and protein is necessary for muscle formation.

Higher inputs are a shock to a system that is slow to respond.

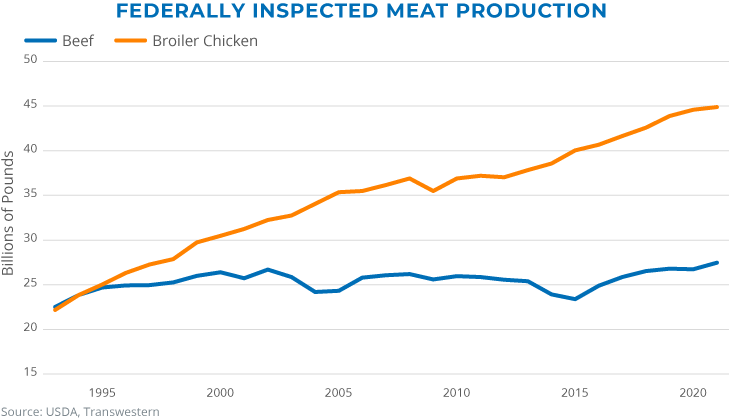

Higher corn costs will trickle into higher costs for finishing cattle which will be passed onto consumers in the form of higher beef prices. Historically, cattle numbers have risen and fallen in roughly 10-year cycles; however, U.S. beef production generally has been declining since 1975 due to the negative health impacts of red meat and the increasing affordability of chicken.

While cattle herds can be reduced quickly, rebuilding takes several years. Much like humans, a cow’s pregnancy lasts nine months, followed by 10 months of weaning, two to three years of stocking in a field, and finally six months at a corn feedlot (finishing beef cattle). This relatively lengthy lifespan means increases in demand take four or more years to be met with increased supply. By comparison, poultry is a much more elastic protein: An egg hatches in three weeks, and a chicken is ready for slaughter 47 days later.

The pandemic caused many meatpacking plants to close and completely disrupted food supply chains Finished meat prices were high due to limited meatpacking facilities and livestock prices crashed as meat could not be processed.

Faced with uncertainty, businesses may settle on the sure thing – chicken.

One effect of supply chain disruptions and inflation is that prices become unpredictable. Prices are the market signal that balances supply and demand. Volatility in price, especially for tight-margin industries, can bring disastrous consequences if improperly managed.

The prices of corn, soy and beef are settled on futures contracts and change depending on economic conditions. But not chicken. While corn and soy are harvested once a year, and calving season is in the winter and spring, chickens are grown year-round. (In fact, there have been multiple attempts to add chicken to futures markets, but with a supply that can respond in weeks there is no need as the price can be settled near real time.)

As Darwin reminds us; it is not the strongest of the species that survives but the one most adaptable to change. And right now, chicken is the nimble protein of the future. It seems the chicken sandwich war will wage on a bit longer.

And a postscript…

Currently, there is an outbreak of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) that is rapidly spreading across the country, driving up egg prices by 50%. Warming weather and the end of bird migration season is predicted to bring this outbreak to an end and populations will quickly bounce back.

In addition, there is widespread drought across cattle country with 80% of the nation’s herd in some category of distress. Rising costs for grain and other inputs will add to the cost of beef production and further fuel the conversion of pastureland to row crops. Once plowed it rarely returns. And those row crops will most likely be soybeans. Soybeans for chickens.

The Los Angeles Research Manager at Transwestern, Thomas Galvin closely follows how the economy and supply chains impact commercial real estate.

SEE ALSO:

- How Borrowers Can Utilize the Debt Yield to Mitigate Risk

- Flexible CPI Points to Potential for High Future Prices

- Expediting Loan Closings in a Blistering CRE Market

RELATED TOPICS:

commercial real estate

real estate

market research

market intelligence